Ancient palm leaf manuscripts are our cultural heirlooms with a wealth of knowledge residing in them. While previous conservation efforts have been made in the direction of digitizing these fragile texts, IIITH researchers have gone a step further and created the first ever large-scale database of such manuscript images that can automatically identify and label different regions of the document. Read on.

Ayurveda and Yoga may have been among the most popular and visible Indian exports to the West, but there exist many more documented shastras or texts on various fields of knowledge, from Science and Technology to Wellness and Ecology. Unfortunately, the early forms of penning down such a vast repository of knowledge existed on materials such as stone, parchment, birch bark and palm leaves – all fragile and fragmented now, thanks to the vagaries of weather and the passage of time.

National Mission For Manuscripts

Palm leaf manuscripts which form the greatest chunk of such early instances of documentation lie scattered across the country in research institutes, temples and even private collections. In 2007, the National Mission for Manuscripts (NMM) launched Kritisampada, the National Database of Manuscripts that contains information about over a million Indian manuscripts. With the help of several resource and conservation centres across India, the goal is to survey and document every known manuscript that lies in the earmarked regions. While the effort is in itself laudable, the digitized images are currently confined to the NMM premises located in New Delhi. It was the thought of making such a treasure trove more publicly accessible that drove Prof. Ravi Kiran Sarvadevabhatla from the Centre for Visual Information Technology (CVIT) to embark on a project of cultural and historical importance. To corroborate his point, he quotes a shloka from the Chandogya Upanishad, “hiranyanidhim nihitam akṣetrajñāḥupari-upari sancaranthah na vindeyaḥ”. Loosely translated as, ‘There is gold hidden someplace underground and people who are ignorant of it walk over that spot again and again, knowing nothing of it (all the while bemoaning their lack of wealth),’ he says that it is allegorical to the current situation where the content in manuscripts are treasures that can benefit humanity immensely, but by remaining untapped, they keep us from benefitting.

Currently there exist very few experts who can read and decipher the fragile manuscripts. In fact, it was one such image of a learned pandit poring over a manuscript with a magnifying lens in hand that is close to Prof. Sarvadevabhatla’s heart. “This is the way great scholars currently look at the written text and try to read it. Some of them are typing them out by hand, which is a very laborious process. I got thinking about how we can have machine learning tools that can aid them,” he says.

Enter Neural Networks

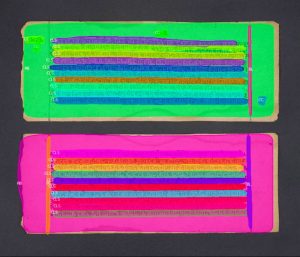

If you’ve looked at a palm leaf manuscript close-up, you’ll know that not only is it difficult to decipher the script or the language it’s written in, but the lines themselves are dense and tricky to follow through. Therefore, in order to have a machine read and convert complex, handwritten manuscripts into printed, editable text, the first step is to let an algorithm identify the layout of the historic images. For this, the team of IIITH researchers obtained digitized manuscript images from two sources. One of them was the publicly available Indic manuscript collection from the University of Pennsylvania’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, also known as Penn-In-Hand (PIH), and the other was BHOOMI, an assorted collection of images sourced from multiple Oriental Research Institutes and libraries across India. Their aim was to maximise the diversity in the selection of the dataset in terms of quality of the document, the extent to which it had been degraded, the script language, the number of lines present in each document, the presence of non-textual elements such as colour pictures, tables, document decorations, and so on. With the help of manual annotations, they trained deep neural networks to automatically identify and isolate different regions of the manuscript images. This is known as instance segmentation. For example, the trained model can now create boundaries around each document, identify each line amongst a set of dense, uneven lines, identify the holes typically punched in manuscripts for binding them together and also demarcate visual images if found in the documents.

Web-Based Tool

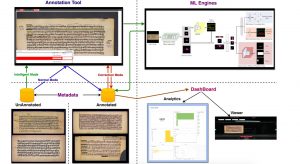

Besides the research itself, Prof. Sarvadevabhatla wanted to make these tools publicly accessible and easy-to-use which will especially be beneficial for other researchers involved in similar efforts. Hence he and his students created an annotation and analysis eco-system. Labelled as HInDoLA, an acronym for Historical Intelligent Document Layout Analytics, it is a web-based system whose architecture comprises of three elements: an Annotation Tool, Dashboard Analytics and Machine Learning engines. The annotation tool, which identifies various components of the document image is configured to work as a web-based service, though it works equally well offline too. It has an ‘intelligent’ system which is integrated with Deep Network-based machine learning models that are both completely automatic as well as semi-automatic. In the semi-automatic scenario, the annotator provides partial annotation in terms of line boundaries and the model takes over by making the complete prediction. The dashboard provides analytics at a glance such as time taken for manual annotation versus automated annotation, live monitoring of the annotation sessions and ability to view various stats in an interactive manner. Feedback garnered from the analytics is incorporated into the machine learning model. Emphasising the user-friendly nature of the web-based system, Prof. Sarvadevabhatla says,” We have taken efforts to make sure the software is easy to install too. For instance, HInDoLA can be set up with a one-click installation.”

While document analysis and recognition exists for handwritten documents, this is the first time that a step in this direction has been undertaken for complex, unstructured documents. It has set the stage for optical character recognition and word-spotting on a large-scale for historic documents. “I am especially happy that in the span of less than a year, my group of undergraduate and MS students have contributed on par with PhD students in overseas institutions. A lot more remains to be done but the efforts represent an auspicious beginning,” says Prof. Sarvadevabhatla.

This research was presented at the 15th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR) 2019, held between 20-25 September in Australia. The work on the web-based tool, HInDoLA was presented in a workshop on Open Software Tools, while the paper on “Indiscapes: Instance Segmentation Networks for Layout Parsing of Historical Indic Manuscripts’ was among the 13% of selected papers for an oral presentation.

More about the research at http://ihdia.iiit.ac.in/

Sarita Chebbi is a compulsive early riser. Devourer of all news. Kettlebell enthusiast. Nit-picker of the written word especially when it’s not her own.

Next post