“She asked for it”. IIITH’s evidence-based research ought to put such statements blaming sexual assault victims to rest.

A study funded by DST’s Cognitive Science Research Initiative and presented at the Cognitive Science Society (CSS) conference 2024 in Rotterdam in July has shown how women experience objectification even in non-sexualised attire. The paper titled, “Objectifying Gaze: An Empirical Study With Non-Sexualised Images” authored by Ayushi Agrawal, Srija Bhupathiraju under the guidance of Prof. Kavita Vemuri of the Cognitive Science Lab at IIITH examines visual gaze with eye tracking technology using the well-known cognitive science theories.

What Are You Looking At?

According to the researchers, while revealing attire is often held accountable for sexual objectification (SO) and harassment, gaze objectification extends to women in even non-sexualized attire. “Regardless of attire, a woman is subjected to a very intrusive gaze in a public or any other space for that matter,” says Kavita, adding that they started on that premise and wanted to test it out. Similar studies conducted in the West have concluded that sexualised images of women attract attention. “It could be any outfit that reveals a lot of skin such as swim wear and they found that the gaze is on the sexual body parts rather than on the face,” she says. The IIITH team on the other hand experimented with images of men and women dressed in a pair of jeans and a shirt. “We did toy with the idea of using salwar-kurtas and/or saris but since the most casual attire that is commonplace these days is the pant-shirt combo, we went ahead with the latter,” explains Ayushi.

What The Researchers Did

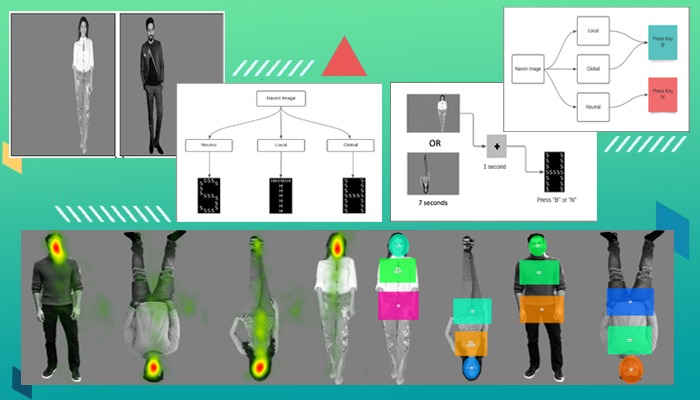

Participants who self-identified as male or female were shown a series of images of both men and women, and their visual gaze was tracked using heat maps. In addition to this, key metrics were analysed such as the total fixation duration – time spent looking at specific areas of interest; either the face or sexual body parts and the visit count – frequency of revisits to these areas. A key difference observed between objectifying gaze in the Western and Indian contexts lies in the focus of the gaze. In Western studies, the gaze often centres more on sexual body parts than on the face, while in the IIITH study, the gaze was on both sexual body parts and on the face. “The Indian population still places a lot of importance on facial features. The evaluation of attractiveness and other social information is all extracted from the face,” explains Kavita. This intriguing finding, where individuals in non-sexual attire were still gaze objectified, suggests that gaze objectification occurs regardless of attire and may be influenced by the social information we first gather from the face. Incidentally, this was found independent of participants’ gender. “It means that both male and female participants were found to be visually objectifying women. When a female objectifies another female, it may mean one of two things,” says Ayushi. “One is self-objectification, internalising socio-cultural attitudes and the second is a social evaluation”. The male gaze on a woman’s body parts is a process of reducing her to an ‘object’ of desire. It has to be noted that male participants also self-objectify as revealed from the study.

Implications

When males objectify females, they dehumanise them by reducing them to mere body parts and often times such objectification is a factor in a sexual assault. “Our research now has data showing us what is normalised in our society,” remarks Ayushi. The broader issue is that numerous factors beyond female attire influence how we perceive, objectify, and mistreat or physically abuse a female. These factors include toxic masculinity, power, social biases and stereotypes, impaired judgement and reduced inhibitions due to substance abuse, pornography, media portrayals of women, and various hormonal or clinical conditions among others. The researchers mention that each of these require detailed studies in the context of the Indian population and larger multi-disciplinary teams working together to develop solutions that drive social-change based on scientific evidence. As a step towards this, in an extension to this study, apart from various kinds of attire, and impact of profession of the females on visual gaze, Ayushi is also examining social stereotypes, toxic masculinity, gender role fixation, the role of social media including sexualised item songs, and the brain activity associated with the empathy felt for rape victims.

“This study was done on a socially aware college-going crowd. If the sample was obtained from a more diverse public, the statistical weights would have been more significant,” says Kavita. While conceding that this research is just a tip of the iceberg and in no way answering all questions, the researchers point out that it’s imperative to analyse all factors that influence the way we perceive others. “The bigger question then is whether these perceptions – of how we look at people – change our empathy. For example, would you have more empathy for a victim of assault who is in a salwar-kurta versus someone in a mini-dress?” Definitely points to ponder.

For more information about the research, click here.

Sarita Chebbi is a compulsive early riser. Devourer of all news. Kettlebell enthusiast. Nit-picker of the written word especially when it’s not her own.

Next post