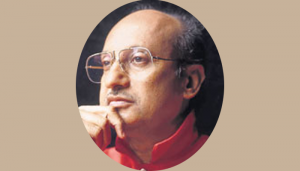

Dr. Sushmita Banerji is the newest faculty addition at the Centre for Exact Humanities. With a Masters in Literature, and an MPhil in Literature-Film Adaptations, she went on to pursue a Phd in Film Studies. When she’s not raving about Iranian and Middle-Eastern cinema, she can be found examining Bollywood “as a cultural entity’. She is currently working on a collaborative book project on film maker Manmohan Desai. The following is an edited excerpt of a conversation where she talks at length on the pervasiveness of the visual rhetoric, ‘difficult’ cinema and Science and Tech in filmmaking.

It’s a question that is unfortunately directed to film studies quite a bit, admits Dr. Sushmita Banerji, when asked if Film Studies refers to the art of making films. She says that in the context of literary studies, people seem to have internalized the difference quite easily. “If I say to somebody, I have a PhD in English, and I teach English, nobody asks if I write a poem. That’s the difference!” she exclaims. For her, Film Studies is about understanding the phenomena. Much like painting, making films is an art. And when one goes to a university to learn about making films, they are awarded a degree in fine arts (MFA). “As a PhD in Film Studies, my job is not to make films, but to read and understand a film, to know what it means in various dimensions”, says Dr. Banerji.

Everyone reads stories. In fact, we start reading rather early, long before we realise and label it as ‘literature’.“A Literature course teaches us a rhyme scheme, or the way a play is divided into Acts and Scenes, or the manner in which we engage with the form, say an essay, or a story, a really long story known as a novel with chapters in it, unlike a short story with no chapters in it. In effect, we are told how to read and differentiate between the different genres of literature,” says Dr. Banerji. Explaining how the visual medium is everywhere and how we watch movies way more than we read stories, Dr. Banerji says that despite watching a lot of film, we are never really taught how to think about it. “From a WhatsApp forward, to a 30-second ad film selling you Coke, to trailers, to TV serials, to NetFlix, to an actual movie with Deepika Padukone in it. These are all stories in an audio-visual medium. We are never taught to think about the language of something that we consume all the time,” she muses.

How did the shift from Literature to Film Studies come about?

When there exists a strong Humanities department at higher levels of academic study like at the PG level, professors have both the intellectual resources and the resources in terms of time to offer interesting courses that are not just core requirements. At EFLU (formerly known as CIEFL), there were enough people in the department to do the core interpretation of Literature and yet have the time to offer courses on Introduction to Indian Cinema, World Cinema, American Cinema, European Cinema. After three such courses, I was hooked! I was always fascinated by difficult films, films that nobody understands..we went through a phase in graduate school. I think it was also part of being a student where you thought you were being fancy if you liked difficult films(!).

Did you grow up watching a lot of movies?

No, not really. I was just like any other kid with restricted TV time, and parents who wanted you to study. My mother has always been interested in serious, alternative cinema. Sunday afternoons used to be movie times with Doordarshan screening award-winning regional movies with subtitles. I would forego my Sunday afternoon nap and stay up with my mother watching these movies. I don’t think I understood much then because I was too little to understand Adoor or Satyajit Ray. My mother was inclined to these movies and was not averse to black and white films or subtitles. So without my knowing it, a bit of groundwork was done. I was also an All India Radio buff and used to listen to a lot of songs. And I had some sense of what was going on in terms of cultural productions. There was an enthusiasm for watching movies but we weren’t exactly going and watching every single movie. And also, this is Jodhpur we’re talking about. Not a lot of great stuff showed up. Certainly not world cinema. That, I started watching once I got to EFLU.

Can you tell us a little about your PhD dissertation.

Various coursework steered me to different kinds of projects. I was interested in certain kinds of film theory such as psychoanalytic literary and film theory, theories of trauma, theories of narration and genre. Partition literature particularly interested me. Typically, cultural production referring to a major traumatic event in History takes time. So not a whole lot was written about the Holocaust immediately after the tragedy. There may have been reports or tallies of people alive or dead, but you didn’t find immediately a novelist writing fiction about the event, a Jewish poet writing a poem about the experience or a film being made directly about the Holocaust. That takes a while. People don’t refer to trauma immediately because they’re still in trauma. That’s something that happened with Indian cultural production as well. If you look at the films of the late ‘40s, or early ‘50s even, there’s no mention of Partition. And the Partition was the largest global migration in the history of the world. But you have an extremely productive film industry which barely mentions it. What was happening at that time, who was writing what, saying what – in cultural production. That was the interesting bit for me. I began to get more interested in the Bengal Partition. And that’s how I veered towards the works of a Bengali film maker, Ritwik Ghatak and eventually did my dissertation on him.

But why Ritwik Ghatak?

The man, Ritwik Ghatak is extraordinarily gifted as a filmmaker. It’s very difficult to find a film maker who is ‘this’ angry, opinionated and concerned and yet so completely in control of his craft that he makes films that are brilliant. The things that he does with sound, editing, and genre – is mind blowing. He doesn’t couch anything or apologize for feeling the way he feels. The fact that I’m a Bengali made it easier to get access to the language, in a way that subtitles and translations don’t quite get. A few films of his stand out above the rest but if I had to pick a favourite it would be this: Shuborno Rekha. Translated as the ‘Golden Line’, it refers to a river which is now dead. It also refers to a golden line between two countries. It’s a family melodrama between a brother and sister who come to West Bengal after the Partition and try to set up a home (they’re refugees). It’s about what it means to make a home and what you learn from the lessons of History. If your understanding of History is skewed, you don’t see the mistakes you’ve made, then you will repeat the mistakes and you cannot make a home again. It ends in tragedy. It’s an extraordinary film and I highly recommend it!

How did you come to IIIT-H?

When I was at EFLU, I had heard that there was something happening at HCU (Hyderabad Central University), they’re starting a tech thing housed in HCU then. When I came back from the US 10-12 years later, it seems to have grown into this place, it’s an adult now, with it’s own land and character among other things. When I was asked for my CV for a position at CEH, I thought this might be a place where I might be comfortable in, even if it is really tech-heavy, primarily because there seems to be an understanding of what one needs to do to let people do their research properly. By and large, find a way in which they can teach their interests. More importantly, they know how to function like a research university which is very encouraging. I think what’s happening in the country now is that most public universities are either being defunded or funding for the Humanities is under a strain. But the premier technical institutes of the country are reaching a point of maturity where they want to be known as not just institutes anymore but as universities. And once you have that aspiration, you realise that to be a university, you need to invest in all kinds of disciplines, otherwise you cannot have real richness of growth. That’s where a few institutes are – like the IITs and IIITs..In understanding that we cannot have solid engineering and research programmes in sciences and technology without acknowledging that knowledge comes from all disciplines.

What courses will you be teaching here?

At the CEH, there is a rubric on ‘Introduction to Gender’ and I was asked if I could teach Gender and Film. I’ve changed the content a bit from what was taught earlier. I’m going to teach gender in literature and film as well. There’s going to be a few weeks of reading different stories, and watching films. Another thing I’m doing at CEH is a module on Literary Studies for the first year students as part of their introductory course to Humanities. And I’m throwing in a bit of film in here as well.

How do you see technology playing a role in Film Studies?

Cinema is an industrial art. Cinema is an easy example to chart where it has to wait around for technology to catch up. When silent black and white movies were made, they would be screened with live music because the film did not have music. There would be players in the pit playing music. They would stop the film and have inter-titles because the film couldn’t ‘speak’. The film maker had to intervene in a different medium and make it ‘speak’. When sound came to cinema, people were then stencilling each frame of film to give it colour so we could have motion film in colour. Then next, we waited around for colour to come to cinema. Cinema depends on technology and Science, and innovation. Having said that, it’s just the form. In terms of research, I’ve had students already approach me to help them. For example, there’s a student who’s doing data management and photography. It would be interesting to see how the next semester shapes up. There are students who want to work on censorship and other things.

How did the interest in Manmohan Desai come about?

My father stopped watching movies in the ‘60s…maybe early ‘70s. And one of the reasons was the shift in the golden era. The ‘70s marks a distinctive shift. The Emergency had happened. You have the angry young man coming out. And from there, you have the multi-starrers, like Amar Akbar Anthony, with three or four heros. Manmohan Desai in a sense, paved the way for the new ‘70s blockbuster – the ‘big’ films which would have Dharmendra and Vinod Khanna and Pran and Ajit and Amitabh Bacchan and three heroines, with 6 songs before the interval, and after the interval, everybody had to fight everybody else and so on. These kind of films moved away from Dilip Kumar and Guru Dutt and Raj Kapoor, away from the idealized hero to a hero who is both funny and a bit of a rogue, street-smart..you don’t have beautiful heroines, singing sad songs ..It was Manmohan Desai who marked this shift. The real answer to your question is, we just had so much fun watching these films! We also realised that nobody had seriously looked at them or done any work on it. It’s a multi-author project. Apart from me, there is Dr. Swarnavel Pillai, Associate Prof in the Dept of English and Media and Information at Michigan State University and Dr. Dennis Hamlin, Asst. Prof at the University of St. Andrews. We are in three different continents collaborating on this.

Sushmita Banerji is serious stuff.

AB says: